Monday, July 30, 2018

by Lizzy Miles

by Lizzy Miles

If you had told me there was a parallel between the study of ninjutsu and hospice a year ago, I wouldn’t have believed you. But I have now realized that there is much to be learned from the ninja philosophy that can be applied to hospice.

It was a patient who helped me make the connection.

The chaplain and I were doing our initial assessment with a cancer patient who was younger than both of us. I will call the patient “John.” I started the visit like I usually do, by asking the dignity question.

“What do I need to know about you as a person to give you the best care possible?”

His response was calm. “I learned in the military, you can gain a lot of strength through suffering. It can help you see through to the other side.”

I looked over at the chaplain, intrigued. I could tell he was intrigued too.

I asked John if he had any worries or concerns. He said it he didn’t. I had heard that one sister was having a particularly tough time, so I asked John if there was anyone in his family that he worried about. Again, in a slow, calm voice, he said, “I hope when I’m gone nothing changes, but a shift in the system can cause disarray.”

I suppose my feelings of surprise were because his manner and presence were so much calmer than patients usually are when they’ve been referred to hospice with a short prognosis. I looked over at the chaplain again and we locked eyes. Craig, our chaplain, has a PhD in Philosophy. I could tell that he was also curious and impressed with John’s demeanor.

I turned to John and told the patient as much. “The chaplain and I are looking at each other because you are a lot calmer and more at peace than most patients we meet. What’s your secret?”

John told us that he had studied ninjutsu.

Though I only met John that one time, his strong presence at that visit affected me. I was so curious about ninjutsu because I really knew nothing about it except what I had seen in movies and television, which couldn’t be more misleading. I searched online, and found an article that introduced me to the spiritual component of ninjutsu training. I then checked out several books from the library and dug in.

According to Dr. Masaaki Hatsumi, the last surviving grandmaster of the ancient art on ninjutsu, there are multiple theories of the evolution and origin of ninjutsu. Going back almost 1,000 years there was a time in Japan where feudal lords ruled through terror. Ninjutsu was created as a martial art focused on self defense against oppressors. Along with the physical training, there was a focus development of mental fortitude (Hatsumi, 1988 p. 19-21).

First and foremost: “The ninja are not members of a circus. Nor are the ninja robbers, assassins or betrayers. The ninja are none other than persons of perseverance or endurance.” (Hatsumi, 1988 p. 77)

Secondly, “…true ninjas began to realize that they should be enlightened on the laws of humanity. They tried to avoid unreasonable conflicts or fighting…The first priority to the ninja was to win without fighting, and that remains the way.” (Hatsumi, 1988 p.23)

What was of greatest interest to me in the books was the details of mental training that went along with the physical training in ninjutsu. Much of what we see in hospice goes beyond the physical as well, and I saw many parallels.

Here are the gems I found:

Ninja philosophy: “The objectives of the ninjas are: first, to use ninjutsu to infiltrate the enemy’s camp and observe the situation.” (Hatsumi, 1988 p. 111).

Ninja philosophy: “The objectives of the ninjas are: first, to use ninjutsu to infiltrate the enemy’s camp and observe the situation.” (Hatsumi, 1988 p. 111).

How it applies to hospice: Everyone involved in a hospice situation, including the patient, their loved ones, and the staff, are observing everyone else.

* The patient often can be stuck in a role of observation whether they chose to or not because they may be too tired to interact, or the family will talk in front of them to staff.

* The family is often on high alert, watching the patient for symptoms or watching the staff and timing our responses.

* The staff members are observing the patient for signs of pain or distress and watching family for signs of psychosocial distress.

Interventions: Be deliberate on the task of observation. Imagine taking the bird's eye view. Sometimes we can be so focused on what we need to do or say that we forget to check in. Make a mental note for yourself to observe before you speak or act.

Ninja philosophy: “In ninjutsu this is no fixed or permanent, ‘this is what it is’. Forget the falsehood of fixed things.” (Hatsumi, 2014, p.46)

How it applies to hospice: This is already my favorite insight with hospice. The longer I’ve been doing hospice, the more I keep learning what I don’t know. I’ve written about assumptions that we have about dying, how the dying may not want to be in control, and the emotions the dying might be feeling. Still, I keep discovering more and more variations in the way that people die – both in timing and symptoms.

Interventions: Be mindful of any time you find yourself feeling certain about a patient’s condition or what will happen. Reflect on the times you have been wrong about what you thought you knew.

Ninja philosophy: “First, forget your sadness, anger, grudges, and hatred. Let them pass like smoke caught in a breeze” (Hatsumi, 1988 p. 123).

Ninja philosophy: “First, forget your sadness, anger, grudges, and hatred. Let them pass like smoke caught in a breeze” (Hatsumi, 1988 p. 123).

How it applies to hospice: It is not uncommon for patients to go through a life review process in which they may have feelings of anger, guilt, or shame. Sometimes they take out their emotions out on us. Friends and family too may have memories of past hurts that come up during this time. Hospice staff are sometimes put in the position where we have to wear a mask to hide whatever might be happening to us outside of work.

Interventions: Work on your awareness of when your feathers are getting ruffled by a patient. Recognize that their attitude towards you may reflect on their own internal state of mind rather than a defect of your own. Be mindful of your reactions to stressful situations.

Ninja philosophy: “We say in Japanese that a presentiment is ‘a message conveyed by an insect.’ For example, when someone is dying, his family or close friends he really loved, can feel something is happening. We say than an insect has conveyed a message to them. It makes us believe that one can communicate through the subconscious” (Hatsumi, 1988 p. 72).

Ninja philosophy: “We say in Japanese that a presentiment is ‘a message conveyed by an insect.’ For example, when someone is dying, his family or close friends he really loved, can feel something is happening. We say than an insect has conveyed a message to them. It makes us believe that one can communicate through the subconscious” (Hatsumi, 1988 p. 72).

How it applies to hospice: If you have been working in hospice long enough, you have to acknowledge there are unusual coincidences, synchronicities, signs, and moments of instinct. There are stories where patients have predicted the timing of their own death, stories about someone dying just when a loved one arrived or left, and stories about spirit presences in the room.

Interventions: Be open to the idea that there are forces beyond what we understand. Remember that patients and families may have belief systems different from our own.

Ninja philosophy: “The first important aspect of ninjutsu is to maintain calmness in the body, and endurance in the heart” (Hatsumi, 2014 p.169).

How it applies to hospice: The connection with this one to hospice seems obvious to me. How many patients do we have with anxiety? From my experience, this feels like one of the most common symptoms across diagnoses, and understandably so. The mind/body connection is most apparent with COPD patients who are short of breath and then feel anxiety about being short of breath and then become even more breathless. We know that they are creating their own cycle, but sometimes we have difficulty helping them find their calm.

Interventions: Start the conversation with patients about anxiety at a time when they are not anxious. Ask them how they calm themselves when they are feeling anxious. If they don’t know how to answer that question, then encourage them to think on it for a while. I sometimes joke with patients that I am giving them “homework.” This goes for staff too. Do you know what brings you calm? How can we be educators if we don’t practice what we preach?

Ninja philosophy: “Nothing is so uncertain as one’s own common sense or knowledge. Regardless of one’s fragile knowledge one must singlemindedly devote oneself to training, especially in times of doubt. It is of utmost importance to immerse and enjoy oneself in the world of nothingness” (Hatsumi, 1988 p. 65-66).

Ninja philosophy: “Nothing is so uncertain as one’s own common sense or knowledge. Regardless of one’s fragile knowledge one must singlemindedly devote oneself to training, especially in times of doubt. It is of utmost importance to immerse and enjoy oneself in the world of nothingness” (Hatsumi, 1988 p. 65-66).

How it applies to hospice: Patients and families do not get to a point of acceptance of death overnight. For patients and families to reach acceptance they need to sit with the uncomfortable feelings. Slowly, they get used to the idea that this is really happening. When patients start sleeping for longer periods of time, both the patient and the family are learning to separate from one another.

Interventions: Be patient with the time it takes for our patients and families to come to acceptance. Realize that for some of them, the introduction of hospice may have been the first time they truly contemplated mortality. They haven’t trained for it like we have. Those who work in hospice and see death and dying on a regular basis can forget what it feels like to be in this situation.

Ninja philosophy: “Ultimately the responsibility for your training is your own” (Hoban, 1988, p. 172).

How it applies to hospice: Remember not to project your own ‘right way to die’ onto a patient. Consider this: some people actually do want to die in a hospital setting! Some patients do want a room full of people there with them. Some people want the television on to Fox news.

Interventions: Ask the patient about their preferences, rather than assuming you know what they want because it’s what you would want. Self-reflect on suggestions you make to patients and families to ensure you're not projecting your own belief system.

References

Hoban, J. (1988). Ninpo: Living and thinking as a warrior. Chicago: Contemporary Books.

Hatsumi, M. (1988). Essence of ninjutsu: The nine traditions. Chicago: Contemporary Books.

Hatsumi, M. (2014). The complete ninja: The secret world revealed. New York, NY: Kodansha USA.

Photos via Unsplash. Some photos have been cropped.

Moon via Clayton Caldwell

Owl via Philip Brown

Butterfly via Nathan Dumlao

Smoke via Alessio Soggetti

Lizzy Miles, MA, MSW, LSW is a hospice social worker in Columbus, Ohio and author of a book of happy hospice stories: Somewhere In Between: The Hokey Pokey, Chocolate Cake and the Shared Death Experience. Lizzy is best known for bringing the Death Cafe concept to the United States. You can find her on Twitter @LizzyMiles_MSW

Monday, July 30, 2018 by Lizzy Miles ·

Saturday, July 7, 2018

“We can focus on your comfort always means we’re giving up.” I can’t count how many times I’ve heard this sentiment from both patients and other healthcare providers, and to read it both frustrated and encouraged me at the same time. It’s frustrating because to know that what I do, as a palliative care physician, to help patients and their families during some of their darkest, scariest, heartbreaking and most painful moments, is seen as 'giving up' when it couldn’t be any more different. Yet, I also find it encouraging because it reminds me that there is much work left to be done on educating everyone on the importance of Hospice and Palliative Medicine (HPM).

“Everything Happens For A Reason and Other Lies I’ve Loved” is Duke Divinity history professor Kate Bowler’s personal perspective on how being diagnosed with cancer disrupted her "seemingly perfect life" and forced her to question what matters most when it comes down to the very real fact that she is dying. Her perspective is real and authentic, and at times unapologetic in its portrayal of her interactions with family, friends, and the medical community. For example, she writes, “She moves through the pleasantries with enough warmth to suggest that, at least on social occasions, she considers herself to be a nice person” describing an interaction during a post-op appointment with a PA. Stories of this nature are always a good reminder that what we do and how we are around patients has a larger impact on them than, we are able to anticipate, or even be aware of.

I find it’s always important to listen to a person’s story, especially when it comes to anything they consider “life-changing,” regardless if that is something we would also agree as being “life-changing.” Perspectives matter, and in healthcare, at times, we can get so caught up with our own perspectives we fail to realize other’s. This is something which doesn’t just affect healthcare providers and Kate is very aware of this as well when writing, “I keep having the same unkind thought – I am preparing for death and everyone else is on Instagram. I know that’s not fair – that life is hard for everyone – but I sometimes feel like I’m the only in the world who is dying”. In a sense she is right, our world is what we see and create with our own eyes and experiences, and Kate is the person “dying” in her world, so to see people who aren’t central to her story living as if nothing is wrong, well I can’t imagine just how frustrating that would be.

As an HPM clinician, empathy is central to what we do. We connect with patients on a different level than many other providers. We seek out - or better yet - we crave that personal connection with patients so we can know and understand what is important to them, who is important to them, and why. We can’t just know the who and what, we need the why, and Kate does an amazing job at sharing enough of her personal life story to allow us to understand why certain decisions in her care are made and also why she views certain interventions, or lack of, as “giving up”. It reminds us that people are a sum of their experiences, and the decisions they make when “push comes to shove” are largely based on those experiences.

I was a bit disappointed after finishing the book, since I assumed the book, given the title, would focus on what healthcare providers, and people in general, should avoid saying to patients dealing with any terminal illness. To my dismay, this was not the case. Sure there are interactions in the book that allow you to see just how “annoying” certain phrases can be, but the majority of the “pearls of wisdom” are left to an appendix at the end of the book. Like, why we should never say “Well, at least…” to any person (or patient) ever.

At the end of the day, if you are a person who is interested in reading the very personal journey of a person facing a very serious and life-changing cancer diagnosis, in an entertaining, heartbreaking yet reassuring and authentic manner, it is well worth the read.

Andrew Garcia MD completed a fellowship in Hospice and Palliative Care at the University of Minnesota in 2018. Interest in include health care disparities around end-of-life care. He likes to tweet at random and can be found on Twitter at @ndyG83

(You can see more of Kate Bowler's writing at her website and blog and podcast. You can also find her on Twitter (@KatecBowler). - Ed.)

(Note- Some links are Amazon Affiliate links which help support Pallimed. We also suggest for you to support your local bookstore. - Ed.)

Saturday, July 7, 2018 by Christian Sinclair ·

Friday, July 6, 2018

We have a 'required reading' list for our fellowship, which includes a bunch of what I think are landmark or otherwise really important studies. One of them is this very well done RCT of continuous ketamine infusions for patients with cancer pain, which showed it to be ineffective (and toxic).

We also recently have seen another high-quality study published with negative results for ketamine. This was a Scottish, multi-center, randomized, placebo-controlled, intention-to-treat, and double-blinded study of oral ketamine for neuropathic pain in cancer patients. The study involved 214 patients, 75% of whom were through cancer treatments and had chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy (CIPN), and the median opioid dose was 0 mg. They received an oral ketamine (or placebo), starting at 40 mg a day, with a titration protocol, and were followed for 16 days.

There were exactly zero measurable differences in outcomes between the groups (on pain, mood, or adverse effects). Zip.

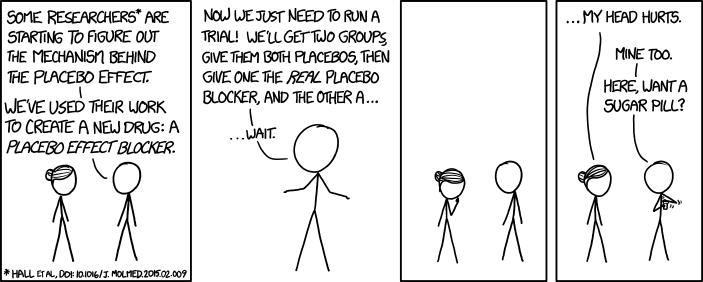

All this got me thinking about a conversation I had with a palliative fellow this year, who, upon reading the continuous infusion study, confronted me with the question - Why do you even still use ketamine, then? The answer to this has a lot to do with the nature of evidence and how that is different for symptom management than it is for other outcomes, as well as the challenging reality of the placebo effect in everything we do.

I should note that you can 'dismiss' these studies based on generalizability (and plenty of people do), i.e., "The infusion study was well-done, but it's a protocol that I don't use, therefore I can ignore it." This very detailed letter to the editor about the infusion study does just that, for instance. Or, that the oral ketamine study was really a study about CIPN, and virtually nothing has been shown to be effective for CIPN, except maybe duloxetine (barely), and so it's not generalizable beyond that, and can be summarily ignored.

All this is valid, to be sure -- it's always important to not extrapolate research findings inappropriately, but honestly the reason I still prescribe ketamine sometimes has little to do with this, and has everything to do with the fact that I have observed ketamine to work and believe it works despite the evidence. Which is a pretty uncomfortable thing to admit, what with my beliefs in science, data, and evidence-based medicine.

Perhaps.

The challenge here is that when it comes to symptom treatments us clinicians are constantly faced with immediate and specific data from our patients as to whether our treatments are working. This is a very different situation than a lot of other clinical scenarios for which we lean heavily on research statistics to guide us. Note that it's not a bad thing we're confronted with this data (!), it just makes it difficult to interpret research sometimes.

Let's start with research which involves outcomes which are not immediate. E.g., does statin X, when given to patients for secondary prevention of myocardial infarction, actually reduce the number of myocardial infarctions (MI) or prolong survival? We can only answer that question with research data because when I give statin X to an actual patient, I have zero way of knowing if it is 'working.' If they don't ever have another MI I'll feel good, but that may take years and decades to even find out. In fact, it's nearly incoherent to even talk about that outcome for my patient, because we think about those sorts of outcomes as population outcomes because that's how they are studied. E.g, we know that if we give statin X or placebo to a population of patients (who meet certain criteria) for Y number of years, that the statin X group will have some fewer number of MIs in it than the placebo group. That's what we know. And because some patients in the placebo group don't have MIs and some in the statin X group do have MIs, we actually cannot even conclude for our own patient whether statin X helped them, even if they never have another MI, because maybe they wouldn't have had an MI anyway. That is, it's a population-based treatment, with outcomes that only make sense on the population level, even though of course we and our patients very much hope that they individually are helped by the drug. Supposedly precision/personalized medicine is going to revolutionize all this, and maybe it will, but it hasn't yet.

Contrast this to symptom management. My patient is on chemotherapy and they are constantly nauseated. I prescribe a new antiemetic -- let's call it Vitamin O just for fun. Two days later I call them up, and they tell me: "Thanks doc, I feel a lot better, no more vomiting and I'm not having any side effects from the med." Or they tell me: "Doc, the Vitamin O just made me sleep all day and it didn't help the nausea one bit." I have immediate, actionable, patient-specific, and patient-centered data at my fingertips to help me judge if the treatment is effective/tolerable/worth it. It feels very different than prescribing statin X, in which all I have is the population data to go by.

So then why do symptom research at all if all we have to do is just ask our patients?

Obviously, it's not that simple, and research is critically important. For one, placebo-effects are hugely important for symptom research, in fact, they dominate symptom research. Blinded and controlled studies are critical in helping us understand if interventions are helpful above and beyond placebo effects (we should all be skeptical/agnostic about any symptom intervention which is not studied in a blinded and adequately controlled manner). Research also helps us get a general idea of the magnitude of clinical effects of certain interventions. Comparative research (of which there's very little, but it's really important) helps guide us towards which interventions are most likely to be the most helpful to our patients. E.g., which antiemetic is most likely to help the largest number of my patients going through a certain situation (so as to avoid painful delays as we try out ineffective therapies)? Research also obviously helps us understand side effects, toxicities -- hugely important.

But...if I thought all of the above were sufficient, I'd still never prescribe ketamine, or for that matter methylphenidate, because the placebo-controlled, blinded studies don't actually indicate they are effective over placebo (let's be honest palliative people, when we actually read the high-quality methylphenidate studies, there's very little there to suggest we should ever prescribe it).

That leaves me though with this belief, based on patient observation, that it still works, damn the data. What do I make of that? I want to be clear, I don't prescribe ketamine a lot, just the opposite, but there are times when you are desperate, you are faced with a patient in an intractable, painful situation, and you're running out of moves to make to improve the patient's life, and the reality is I sometimes will prescribe ketamine then, and my observation is that it's sometimes hugely helpful, enough so that I keep on using it.

And I honestly don't know what this represents - is it that complex phenomenon called the placebo-effect that decides to show up every now and then (although for these patients you wonder why the placebo-effect didn't show up on the 5 prior treatments you threw at them)? Is it that I'm 'just' making them euphoric and I'm not actually helping their pain (although honestly, I think it's impossible to draw a hard line between the two)? Or is it the fact that for presumably complex genetic neurobiological reasons, while ketamine is ineffective toxic for the majority of patients out there, it is also really effective/well-tolerated for a minority of our patients, and that's the sort of thing that it's tough to parse out in trials, because the small number of responders is overwhelmed by the strong majority of non-responders.

I like to tell myself it's the latter, although I need to admit that probably a lot of the time it is placebo-effects. None of us should be happy about prescribing drugs with real side effects, and we must recognize the possibility for patient harm 'just' for placebo effects. (Which, incidentally, is why I'm perfectly ok using lidocaine patches sometimes even when I just assume it's a placebo - because of the near zero chance of harm to the patient. True confessions.)

But, to emphasize my point, if it is the latter (some drugs like ketamine and methlyphenidate do actually really help a minority of patients but are toxic to most and so it's tough to appreciate the impact based on clinical trial research), that emphasizes the critical observation about why high-quality clinical research is important - it helps us know which interventions we should be doing routinely and early, and which should be at the bottom of the bag, to be used rarely, and with great consideration.

But, given that this is true confessions day, I still don't think methylphenidate is something to be rarely used. In fact, it's one of the few things I do in which I routinely have patients/families enthusiastically tell me thank you that made a huge difference. (If you're curious those things are 1) talking with them empathetically and clearly about what's going on and what to expect with their serious illness, 2) starting or adjusting opioids for out of control pain, 3) olanzapine for nausea, and 4) methylphenidate.) Like, all the time. Like, they come back to see me in a couple weeks with a big smile on their face, so glad I started the methlyphenidate. Happens a lot (not all the time, but enough of the time). A lot more than with gabapentin or duloxetine or many other things I also prescribe all the time which have 'good evidence' behind them. It happens enough that I've asked myself What data would convince me to stop prescribing it to my patients? And I don't have an answer for that, apart from data suggesting serious harm/toxicity (which none of the RCTs have shown).

I'm very curious as to people's thoughts about all this and look forward to hearing from you in the comments!

Drew Rosielle, MD is a palliative care physician at the University of Minnesota Health in Minnesota. He founded Pallimed in 2005. You can occasionally find him on Twitter at @drosielle. For more Pallimed posts by Drew click here.

Friday, July 6, 2018 by Drew Rosielle MD ·

Saturday, June 30, 2018

Let's just stop doing this.

There has never been any actual evidence that palliative care (PC) interventions improve survival in patients, but since the landmark Temel NEJM 2010 RCT of early outpatient palliative care for lung cancer patients showed a clinically and statistically significant improvement in longevity in the PC arm, I have heard and all read all sorts of statements by palliative people and all sorts of others (hospital executives, policy makers, oncologists) in all sorts of venues (local talks, national talks, webinars, newspapers, etc) along the lines of 'palliative care helps patients with cancer live longer.' I've even heard the results discussed as evidence that hospice helps cancer patients live longer.

We should have never done this, and if you're still doing it, please stop.

To begin with, 'palliative care' isn't a single thing. It's not like studying enoxaparin, or nivolumab, or olanzapine, where you can to a reasonable extent assume that if it helps patients in Lille, France or Boston, MA, it will likely help your similar patients in your practice wherever. Palliative care is just not like that - it is complex, and local conditions are very important, and it is impossible to make broad generalizations about PC in general from a single study at a single institution. Some PC research involves full interdisciplinary teams doing their thing; some are one or two disciplines; some involve telemedicine, care coordination, etc. You just can't generalize these sorts of interventions to 'PC' in general because it can mean so many different things.

Plus, the Temel study was only a single disease, and their nicely done follow-up study which broadened the patient population presumably failed to show any survival difference (because they haven't published that result that I'm aware of).

There is an exceedingly thin quantity of additional PC research showing improved survival. Most importantly I think is Bakitas' ENABLE III study which, notably, did not compare PC to usual care but early PC to PC 3 months later in cancer patients and showed prolonged survival. Curiously, it didn't show any difference between groups in any other outcome (not in QOL, symptoms, intensity of EOL care, chemo in the last 14 days of life, hospice enrollment)! There is this secondary analysis of the study arguing that the survival benefit was mediated by depression, which sure maybe, except that the actual stable itself didn't show any change in mood between groups. So, it's messy, right, and at the end of the day one is left thinking that the survival improvement is curious, and you don't really know what to make of it (and not left to strongly endorse broad, unqualified claims that PC makes people live longer).

There is also this somewhat famous study purporting to show that hospice extends survival in CHF and cancer patients. Besides being industry funded (NHPCO) and using data that are nearly 20 years old now, it uses a statistically complex, opaque, retrospective design using Medicare data, that is really difficult to understand for us non-biostaticians. It's a tough question to study after all -- without randomization which would be ethically and practically challenging, how do you compare survival in patients without a clear time zero. I.e., if time zero is when someone enrolls in hospice, what is the comparable time zero for someone who never enrolls in hospice? How do you capture them at the time when they are 'equally sick' to someone who happens to enroll in hospice. You can't, thus the statistically complex study design. I'm not criticizing the study, but I am very much arguing that it's not the sort of research we translate into broad claims that 'people live longer on hospice.'

The vast majority of studies of PC intervention either don't report survival, or if they do have a neutral affect on it. Although it's notable that while everyone knows about the Temel 2010 study, hardly anyone mentions the really well done randomized, controlled trial of home-based palliative care which showed all these great outcomes (patient satisfaction, health care utilization), but also, oops, showed shorter survival in the palliative care intervention group. (You can enjoy this cranky letter to the editor about this written by Andy Billings and Craig Blinderman, as well as the authors' response, here. I really miss Andy's constant, erudite crankiness.)

Given how heterogeneous PC is, what would constitute adequate evidence that 'PC' actually prolongs survival? I think it would be one of two things, neither of which exists.

One would be a large number of single institutional studies of PC interventions which show prolonged survival (and, concomitantly, an absence of numerous single institution studies showing the opposite). How many? I don't know, but a lot more than we have now. Think about how many studies we have of PC interventions, from all over the world, in different patient populations, inpatient and outpatient, including both trials and observational research, which show improvements in some patient-centered outcome like quality of life. A lot, so many in fact that it's notable when one doesn't show such an outcome. We don't have anything close to this for survival outcomes.

In fact, someone went ahead and did a very nice meta-analysis of all these (mostly single institution) palliative trials, which shows just how great we are at improving all sorts of awesome outcomes, just not survival.

The second would be a large, multi-institutional, multi-regional study of some sort of PC intervention showing improved survival. That doesn't exist. We do have it for resource utilization - such as this multi-regional study by Sean Morrison published in 2008. Additionally, resource utilization outcomes are like QOL outcomes - they are a dime a dozen (we have dozens of studies of PC interventions, of many different shapes and sizes, from all over the world, showing differences in resource utilization).

At the end of the day I of course hope PC interventions prolong survival, but I'd be pretty surprised if that panned out. Most of our patients want to live longer with a reasonable quality of life, and I think we should be satisfied with the 'helping them have better QOL part.' We should react with curiosity about any new single-institutional study which shows improved survival, just as we should with similar studies that show decreased survival. Not anything to celebrate or bemoan.

Thing is, we have a lot to be proud of. A lot that we do well, and that we have all sorts of evidence supporting us in. Without qualification, we can go around saying Palliative care improves the quality of life of patients with serious illness. Seems good enough to me.

Drew Rosielle, MD is a palliative care physician at the University of Minnesota Health in Minnesota. He founded Pallimed in 2005. You can occasionally find him on Twitter at @drosielle. For more Pallimed posts by Drew click here.

Saturday, June 30, 2018 by Drew Rosielle MD ·

Thursday, June 14, 2018

by Lizzy Miles

by Lizzy Miles

It has been four years since I first wrote the article “We Don’t Know Death: 7 Assumptions We Make about the Dying” for Pallimed. You would think that with four more years of experience I would feel more confident in my knowledge about my job and my patients. I don’t.

In fact, I’m still uncovering assumptions that I make when working with patients who are dying.

Recently, I discovered Assumption #8: Dying patients want to be in control.

I had so many reasons and examples to believe this, from the very beginning of my hospice work. I came to this conclusion after just a short time volunteering. One of the hospice patients I visited would have me adjust the height of her socks continuously for ten to fifteen minutes. At first I didn’t understand and I thought to myself that she must be a little obsessive. Then I had this a-ha moment.

She can’t control the big things, so she wants to control the little things.

This assumption held up for a while. I would have frustrated caregivers who would tell me that their dying loved one was impossible and demanding over little stuff: the lights in the room, the arrangement of the drapes. These caregivers would be exasperated. I would validate their feelings of frustration, but also encourage them to empathize. I’d tell them that it’s tough to be dying. The dying need to control what they can. Often this worked to provide some relief to the caregiver, if only briefly.

Slowly, though, my solid belief in the dying person’s desire for control began to unravel. True, there are some patients who still very much want to be in control…but not everybody.

Everything came to a head when I met “John.” I asked him the dignity question, like I always do. He scowled at me.

“How dare you ask me such a deep question. How am I supposed to answer that?” His was one of the most difficult assessments I had to make because he didn’t like questions. He told me his wife asked too many questions. He told me he wasn’t doing well, but “there’s no point to talk about it.”

“How dare you ask me such a deep question. How am I supposed to answer that?” His was one of the most difficult assessments I had to make because he didn’t like questions. He told me his wife asked too many questions. He told me he wasn’t doing well, but “there’s no point to talk about it.”

Later that day, his wife (I’ll call her “Sally”) came into the inpatient unit, and I returned to the room to meet her. We sat on the couch across the room while John was finishing a visit with a Pastor. Sally talked about how sweet John used to be. She said lately though he had been taking his anger out on her. We had moved to his bedside when Sally said to me, “All I ask is whether he wants bacon or sausage and he yells at me.”

At this point, John rolled his eyes.

I looked at him, and then after reviewing our first interaction in my head, it dawned on me. He is overwhelmed. Unlike other patients who want to control every little thing, John was irritated by the decisions he had to make. I turned to Sally and said, “I know you are trying to please him and give him what he wants, but right now, he has the weight of the world on his shoulders. The act of deciding whether he wants bacon or sausage is so insignificant to him right now.”

I looked over and John was nodding vigorously. Sally was listening intently. “But what do I do? I want to make things easier for him.”

Side note: Surprisingly, we can learn things from television medical dramas. I had been watching The Good Doctor and there had recently been an episode about how a doctor with Asperger’s was irritated with being asked questions. Another doctor realized that giving him statements, rather than questions, are better.

So I suggested to Sally. “Don’t ask him whether he wants bacon or sausage. You pick what you’re making and tell him, ‘I’m going to make you bacon and eggs.’ If he doesn’t want that, he will let you know.

So I suggested to Sally. “Don’t ask him whether he wants bacon or sausage. You pick what you’re making and tell him, ‘I’m going to make you bacon and eggs.’ If he doesn’t want that, he will let you know.

John nodded vigorously again and said emphatically, “Oh yeah I would.” Both were smiling. We were then able to move on to life review and by the end of the visit, the grumpy patient was calling me “Darling.”

So how do you navigate learning and understanding patient preferences to have control or give up control? They aren’t always able to tell you but it's not hard to figure out if you're looking for it. Generally, I would say to start with the premise (okay yes, assumption) that they do want to feel in control.

For the patient who wants control:

- Frequently reinforce that they are in charge.

- If the family tries to take over conversation, always look to the patient until the patient verbally defers. (One exception is if there is a cultural component that an established family point person represents the patient).

- Ask permission before you sit.

- Ask permission to visit.

- Don’t assume they want the television or the lights on/off. Ask.

- Consider how you might get information by making statements instead of asking questions. Say: “I wondered how you were doing today.” If you raise your voice at the end of the statement, it’s still a question. Try saying the statement and then sitting with the silence. A non-answer might be an answer in itself.

- If you get more than one “I don’t care” as an answer to a question of choice, be mindful of decision fatigue. Tell the patient what you’re going to do and leave space for them to state a preference.

- Listen for cues from the family indicating that they’re having newfound interpersonal communication issues and provide education when appropriate.

- Know that when patients express untruths ("lies") it might be a sign of question fatigue.

Photo credit: trees by Evan Dennis on Unsplash

Photo credit: breakfast by Karolina Szczur on Unsplash

Lizzy Miles, MA, MSW, LSW is a hospice social worker in Columbus, Ohio and author of a book of happy hospice stories: Somewhere In Between: The Hokey Pokey, Chocolate Cake and the Shared Death Experience. Lizzy is best known for bringing the Death Cafe concept to the United States. You can find her on Twitter @LizzyMiles_MSW

Thursday, June 14, 2018 by Lizzy Miles ·

Friday, June 8, 2018

Anniversaries are a fun time to celebrate, but the fun ones end in numbers in 0 or 5. For other anniversaries, it is a good time to take stock, reflect on the past and look towards the future.

Today is our 13th anniversary of Pallimed, which Dr. Drew Rosielle started in 2005 when blogs were THE thing to do in social media. We also spent many of those early years helping people understand the power of communication through social media with projects like #hpm chat on Twitter, encouraging tweeting from conferences and the advocacy power of our Pallimed Facebook page. With that focus, we have drifted away from original content being the main thrust of our efforts, but have still strived to create good content with strong posts from great writers like Lizzy Miles and Drew Rosielle among others. We are still dedicated to the website and will continue to post always.

Of course, this effort does not happen without the work of many people. I am indebted to Lizzy Miles (Pallimed editor), Megan Mooney-Sipe (Lead Facebook Contributor), Meredith MacMartin and Renee Berry (#hpm chat) for leading some of the core projects of Pallimed. A big thank you to other volunteers who have helped with various projects in the past year including: Jeanette Ross, Kristi Newport, Ashley Deringer, Gary Hsin, Joe Hannah, Lori Ruder, Niamh van Meines, Emily Escue, Ben Skoch, Jen Bose, Liz Gundersen, David Buxton, SarahScottDietz, Sonia Malhotra and Vivian Lam.

Since Pallimed has always been a volunteer effort, we are of course on the lookout for great new volunteers to join us and if you have been a part of Pallimed in the past, we would always welcome you back. If you have a great idea for a series of posts, podcast, videocast, journal club, book review, film review, journal article review, this is a great place to publish it. If you are not the creative type, there are a ton of admin projects that need to get done behind the scenes. Many hands make light work and I can tell you it is a blast being part of a team that makes a big difference...together. We have an audience of over 50,000 across all of our platforms so if there is something that needs to be said, we can help you say it. If you are not sure what to say, I have plenty of writing assignments where I am looking for writers. As a bonus, this work can be used for academic promotion if that is something you need. I've seen work for Pallimed get cited in promotion applications!

So the state of the blog is steady. We are staying the course, but always on the lookout for other smart, dedicated, passionate people who want to make a difference for palliative care and hospice. Let me know if that is you.

Christian Sinclair, MD, FAAHPM is the Editor-in-Chief of Pallimed. He is always surprised he wrote the most for Pallimed when he had infant twins in his house.

Friday, June 8, 2018 by Christian Sinclair ·

Wednesday, June 6, 2018

The American Society of Clinical Oncology annual meeting, besides being a feast for the pharmaceutical business news pages (google 'ASCO' and most of the hits will be about how announcement X affected drug company Y's stock), is also one of the premiere platforms for publishing original palliative-oncology research. So every year I try to at least scan the abstracts to see what's happening, and I figure I might as well blog about it. It's tough to analyze abstracts, so I'll mostly just be summarizing ones that I think will be of interest to hospice and palliative care folks. I imagine I've missed some good ones, please leave a link in the comments if I have! My major observations on this year's abstracts is that there was very little about symptom management compared to years past, except for neuropathies.

(Past ASCO reviews here - 2008, 2017 - Ed.)

Fatigue/Nutrition

- A negative phase 2 study of a walking intervention for fatigue in patients with breast cancer

- A look at 10-year trends in TPN use in cancer patients (use is slightly declining, as are costs, and involvement of palliative care is increasing)

- Parenteral nutrition once again fails to show any benefit over oral feeding for cancer cachexia (and in fact suggested harm)

- A nice study looking at the determinants of long-term fatigue in patients with treated ovarian cancer

- Perhaps the microbiome influences cancer-related fatigue?

- Code status, race, and palliative care involvement at a single institution in Texas

- A small study that showed that training oncologists in communication skills (it's implied that it's with Vitaltalk methods, although that's not exactly clear from the abstract) does increase the use of those skills in real life, but did not increase the amount of goals of care conversations, etc.

- A project to disseminate palliative care knowledge in multiple Sub-Saharan African countries

- A fascinating prospective study looking at dis-/concordance between patient and oncologist perception of care goals over time. Another abstract from this study showed that concordance did seem to matter at least for patients with 'aggressive' goals (they got what they wanted if the oncologist understood that goal). I hope they write this up for full-publication, as I want to know more.

- Apparently palliative celiac plexus radiosurgery is a thing

- More frustratingly inconclusive data about the 'Scrambler' device for chemo neuropathy (it was randomized against TENS, unclear if anyone was blinded, results were barely positive for Scrambler). Perhaps I'm just totally ignorant, but I don't understand why no one can do a double-blinded sham-controlled study of the technology. Actually at this point I'm just assuming because it's not effective and that's why, but I don't really know. [Late edit - hey, I guessed right, a sham-controlled study showed Scrambler probably doesn't help, and you can sense the disbelief and desperation in this curiously-written abstract.]

- Omega-6 fatty acids reduced pain more than O-3 fatty acids in breast cancer survivors in a randomized & blinded (but no placebo-arm) study. Interesting, but I just can't imagine that we are ready to study this without a placebo arm yet!

- An uncontrolled mindfulness study on chronic cancer pain shows promise

- A look at the natural history of chronic pain in survivors of childhood cancers

- Low-quality, retrospective look at cannabis and QOL/symptoms in patients with cancer

- Investigations into cryotherapy to prevent chemo neuropathy stumble along

- RCT of a novel superoxide dismutase mimetic to prevent radiation mucositis in Head and Neck cancer patients with promising results

- Claims and SEER database study suggesting that earlier palliative care involvement in pancreatic cancer reduces some costs.

- Patients in Medicare managed care organizations use hospice a little more than fee for service Medicare patients

- Barriers to palliative care involvement in patients receiving stem cell transplants, including this data point, which is something I've personally wondered about a lot: "Higher sense of ownership over patients’ PC issues (β = -0.36, P < 0.001) was associated with a more negative attitude towards PC [by hematologists]."

- EOL spending was higher in ACO patients vs non-ACO patients.

- A retrospective study which compares many outcomes in patients who receive early palliative care inpatient vs not. The title abstract highlights survival (which was a bit longer in the palliative group). Please do not quote this abstract however to claim that PC prolongs survival in patients with cancer: this is messy retrospective data, and it's not even clear from the abstract whether the survival difference was in univariate or multivariate analysis (PC patients, eg, were younger, more likely to be discharged home, etc.). Similarly, a Canadian study looked at early palliative care consultation in pancreatic cancer (retrospectively) and apparently showed that late but not early palliative consultation was associated with longer survival. The same study also showed that having metastatic disease at the time of diagnosis was also associated with longer survival, so I'm not going to make much of any of this.

Drew Rosielle, MD is a palliative care physician at the University of Minnesota Health in Minnesota. He founded Pallimed in 2005. You can occasionally find him on Twitter at @drosielle. For more Pallimed posts by Drew click here.

Wednesday, June 6, 2018 by Drew Rosielle MD ·

Friday, May 25, 2018

So, to help answer these question, we at Pallimed and GeriPal have created a quick guide to the top 5 resources we use to prep for the boards:

- AAHPM's Intensive Board Review Course: the ultimate live in-person prep that includes a pretty stellar cast of speakers including Mary Lynn McPherson, Kim Curseen, Sandra Sanchez-Reilly, Joe Shega, Drew Rosielle, Michelle Weckman, Scott Schwantes, Janet Bull, Jeff Spiess, and Gregg VandeKieft. The course takes place this August 9-11, 2018 in Minneapolis, MN, and will include both lecture-based content plus lots of exam-type questions to help you pass the test (and brush up on your hospice and palliative care knowledge). Plus you get to hang out with a bunch of cool palliative care colleagues.

- The Pallimed/GeriPal Blogs to Boards Questions: yes, it's slightly dated but hey, so are the exam questions (it takes a couple years for the exam questions to get into real life circulation). Plus, the great thing about these questions is that we can update them on the fly. So if you notice a question or answer that needs updating, send the edits our way and we will make the changes. Questions Only Handout; Questions and Answers Handout

- Essential Practices in Hospice and Palliative Medicine: For those who've been in the field for a while, you may remember the book series called "UNIPAC". This was our go-to resource when studying for the boards 10 years ago, and remains so today, just with a different name. It's a comprehensive 9-volume self-study tool that has been completely updated for its rebranded "Essentials" name. Plus it comes with an online confidence-based learning module to test your level of knowledge and level of confidence in each topic area presented in the book series.

- Fast Facts: a great, free resource for a quick how to for over 350 palliative care issues.

- HPM PASS: Need more exam questions. Get AAHPM's HPM PASS for an additional 150 questions.

We would love to hear what other resources you have used and found helpful. Add them below to the comments section at either the GeriPal or Pallimed websites.

Thanks!

The folks at Pallimed and GeriPal

Friday, May 25, 2018 by Christian Sinclair ·

Sunday, April 22, 2018

Join the #hpm Tweet Chat This Week in a Research Initiative with the Brain Cancer Quality of Life Collaborative

The Pallimed community is invited to participate in the #hpm Tweet Chat this week which help inform and shape a comparative effectiveness research proposal being designed by the Brain Cancer Quality of Life Collaborative, an initiative led by a team of patients, care partners, advocates, neuro-oncologists, and palliative care professionals.

The #hpm Tweet Chat is this Wednesday, April 25th, 6-7p PST/9-10p ET.

Topics for the chat are available here, in the #hpm chat’s blog post, How might we introduce palliative care to people with complex neurological conditions, by Liz Salmi and Bethany Kwan, PhD, MSPH.

In October 2017, the Collaborative was awarded $50,000 from the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI), to drive improvements in palliative care experiences for patients with brain cancer and their families.

With the belief that families want to spend time building memories, not navigating the healthcare system, topics for the #hpm chat week were shaped by Bethany Kwan, PhD, MSPH, and Liz Salmi.

Bethany Kwan, PhD, MSPH, is a social psychologist and health services researcher at the University of Colorado School of Medicine and a daughter and care partner of a person who had glioblastoma. Liz Salmi is a communications professional with expertise in design, community organizing and digital communications. Liz has been living with grade II astrocytoma since 2008, blogs at TheLizArmy.com and when she isn’t talking about brain cancer, she’s working on OpenNotes, an international movement focused on making health care more transparent.

Here is a Twitter list of the leaders in the Brain Cancer Quality of Life Collaborative and a photo below.

Join #hpm chat this week! We're discussing #palliative care for people with complex neurological conditions as a part of a #research initiative! #btsm All are welcome to join! Wed April 25th, 6p PST/9p ET, learn more: https://t.co/afvy37Qo0X pic.twitter.com/bQRGts8eAa— HPM Chat (@hpmchat) April 22, 2018

Sunday, April 22, 2018 by Unknown ·

Monday, March 12, 2018

The Annual Assembly of AAHPM and HPNA is this week and if you are going to Boston, or staying home to keep things running smoothly, social media can help make your conference experience be transformative. Since 2009, the Assembly has been making use of Twitter to provide additional insight, commentary and sources for the multiple sessions each day. Now things are expanding to dedicated conference apps, Facebook and Instagram. And for the first year ever we have Twitter contests.

The official hashtag of the conference: #hpm18 (works on Twitter, Facebook, Instagram), use it in every tweet this week! (Are you wondering why the hashtag for our interprofessional field/assembly is #hpm and not #hpc? Read more here.)

Pallimed Network Accounts

- Twitter (@pallimed) - run by Allie Shukraft, Kristi Newport and Christian Sinclair during the conference

- Twitter (@hpmchat) - run by Lori Ruder and Ashley Deringer during the conference

- Facebook - run by Megan Mooney-Sipe and our volunteer team

- Facebook event page (#HPMparty) - Team effort with GeriPal

- Instagram (@pallimedblog) - run by Christian Sinclair, with behind-the-scenes looks using Instagram Stories

- Website

American Academy of Hospice and Palliative Medicine:

- Twitter (@AAHPM)

- Facebook Event page

- Instagram (@AAHPM)

- Website

- CONNECT Forum

- Temporarily change your Facebook Profile to have a #hpm18 frame

Social Work Hospice and Palliative Care Network (Not part of the Assembly, but having a conference right before)

Monday, March 12, 2018 by Christian Sinclair ·